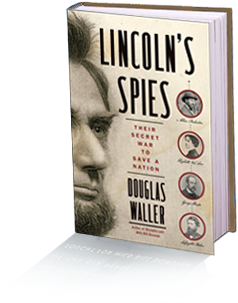

A conversation with Douglas Waller, author of LINCOLN’S SPIES: Their Secret War to Save a Nation

Q. In a nutshell, what is Lincoln’s Spies about?

Q. In a nutshell, what is Lincoln’s Spies about?

Lincoln’s Spies is the story of espionage and counterespionage operations in the Civil War’s Eastern Theater. It’s told through the lives of four secret operatives working for the Union: Allan Pinkerton, Lafayette Baker, George Sharpe and Elizabeth Van Lew. Of course, there were intelligence operations in other parts of the country. But the Eastern Theater, where these four agents fought, became a crucial region of the war. The area included the capitals for the belligerents—Washington and Richmond—and was the site of many of the largest and costliest battles of the war. Pinkerton ran intelligence operations for Union General George McClellan. Baker ran counterespionage operations in Washington, D.C. Sharpe succeeded Pinkerton and ran intelligence operations for the Army of the Potomac and for General Ulysses S. Grant. Van Lew organized a Union espionage ring in Richmond.

Q. Why did you decide to write this book?

I covered the CIA for a number of years for Newsweek and then TIME magazine. My last two historical biographies were of major intelligence figures during World War II. One book was on Wild Bill Donovan, who headed Franklin Roosevelt’s spy service, the Office of Strategic Services, and the other was on four men who worked for Donovan in the OSS and later became CIA directors: Allen Dulles, Richard Helms, William Colby and William Casey. For my next book, I decided to switch wars and write an ensemble biography of four Union spies during the Civil War. And I’m glad I made the switch.

Q. Why did you pick these four Union spies as the main characters for your book?

I did so for several reasons. I found the Union operatives to be far more interesting than their Confederate counterparts. Two of my spies—Sharpe and Van Lew–were heroes in the war. Pinkerton was a failure. And Baker was a scoundrel. So I had a pretty good mix here. Also, Civil War movies often have the Rebels outperforming the Yankees in espionage. But that really wasn’t the case. For most of the war the Yankees had a much more comprehensive and effective intelligence gathering operation than the Confederates ever fielded. So by the end of the conflict Ulysses Grant actually had a better count of Robert E. Lee’s forces than Lee had.

Q. What was special about intelligence collection during the Civil War?

I discovered that beneath the surface of this vast war between the North and the South a revolution was occurring in military intelligence collection—in the way armies spied on one another. That’s what I found fascinating as I dug more deeply into this subject. Of course there was the traditional cloak and dagger work we’ve seen in previous wars. Each side sent scores of spies into the other’s territory to try to steal secrets. But new war-making technology also ushered in new types of spying. With the advent of the telegraph, signal intelligence became important in this war. Today it’s called SIGINT in spy jargon. Back then it was reading the enemy’s messages that were tapped out in Morse code over the line. Photography was soon found to be a useful spy tool. Photographers joined the Union army to covertly take shots of enemy troop encampments and future battlefields. We saw aerial reconnaissance used often in this war. Hydrogen gas-filled balloons, mostly on the Union side, were sent into the air as high as 1,000 feet with aeronauts dangling in their wicker baskets to scope out the battlefield ahead or direct artillery fire on a target. These were the forerunners of the spy planes and satellites we have today.

Q. What did Abraham Lincoln think of these spies?

He appreciated them. Abraham Lincoln may have been called “Honest Abe,” but he was hardly a neophyte when it came to the dark arts of subterfuge and intrigue. Before becoming president he often wrote news columns under aliases to attack opponents. During his race for the presidency, he was a careful reader and evaluator of political intelligence. Once in the White House, Lincoln ordered General Winfield Scott to deliver him daily intelligence reports on the enemy. He prodded his military commanders to accept new war-fighting technologies, like balloons for areal reconnaissance. He had no qualms about launching risky covert operations against the South and found subversion and propaganda useful tools. Lincoln could also be ruthless when he felt he had to be, suspending the writ of habeas corpus, allowing arbitrary arrests of thousands, and shuttering newspapers considered hostile to the administration’s war aims.

Q. How did you conduct your research for Lincoln’s Spies?

Unraveling the spying that really went on during the Civil War became a treasure hunt. Tens of thousands of books have been written on that conflict, but the reliable ones on its espionage and covert operations are few and far between, I soon discovered. A number of men and women wrote postwar accounts of their spying, which turned out to be fabricated. Many of the true spies, like Allan Pinkerton and Lafayette Baker, embellished their stories in postwar memoirs. Myths have been passed down from generation to generation and today are still accepted as true. So separating fact from fiction became the first challenge in writing Lincoln’s Spies.

I spent months at the National Archives and Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., rooting through hundreds of thousands of documents stored there for evidence of clandestine activity during the Civil War. I visited libraries and archives all over the country to collect material on my four main characters. I toured the battlefields of key engagements—such as at Antietam, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg—to get an on-the-ground feel for the fighting and the intelligence collection affecting their outcomes. I also managed to track down distant relatives of some of my characters, who shared with me family stories and documents from their personal collections.

Q. Which Union spy interested you the most?

As has been the case with my previous biographies, Lincoln’s Spies put me deep inside the lives of Allan Pinkerton, Lafayette Baker, George Sharpe and Elizabeth Van Lew. Reading their writings, personal letters, and government documents about them, I grew close to all four of them and found their characters fascinating. Allan Pinkerton was a strong-willed and dour workaholic, who unfortunately was out of his depth as spymaster. Lafayette Baker was a colorful scoundrel. George Sharpe was a highly educated officer, who was a pioneer in military intelligence collection, yet there was still a bit of fun in him. Elizabeth Van Lew was a fearless spy, and a champion of African American civil rights at a time in Richmond when holding those views could get you tossed into prison or even lynched.